Download: PDF

Download: .PNG image

Use Policy: Free for personal and church use. Not for sale or commercial distribution.

Author: Neil Baulch

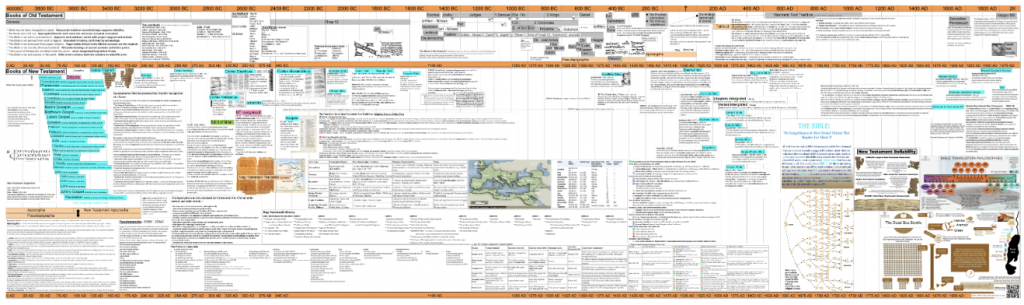

How to Read the “How We Got Our Bible” Chart — From Revelation to Your Translation

Purpose: explain how to read your Bible Formation chart, show how each panel fits together (revelation → inspiration → canon → preservation → textual criticism → translation → today’s usage), and give you a reproducible workflow to teach or study it—without drifting from a conservative, grammatical-historical approach that honours Scripture’s authority.

1) What This Chart Is (and Is Not)

What it is: a single-page map of how God’s word moved from God to us:

Revelation (God speaks) → Inspiration (God-breathed Scripture) → Recognition/Canon (God’s people receive and recognise the books God gave) → Transmission/Preservation (scribes, copies, manuscripts) → Textual Criticism (careful comparison of copies to recover the earliest text) → Translation (Hebrew/Aramaic/Greek into living languages) → Publication and Use (reading, preaching, discipleship).

What it is not: a defence of any one English translation, nor a story of perfect scribes or magical processes. God gave an inerrant word in the autographs; He has faithfully preserved it in the manuscript tradition so that we possess the word of God reliably today (2 Tim 3:16–17; Matt 5:18; Isa 40:8; 1 Pet 1:24–25).

2) The Big Picture: Four Rings and a Timeline Rail

Think of the chart in four rings wrapped around a left-to-right historical rail.

Ring 1 (Core): Revelation & Inspiration (God → Prophets/Apostles → Scripture)

- Revelation: God discloses truth we could not discover unaided (Heb 1:1–2; Exod 34:6–7).

- Inspiration: “God-breathed” graphe (Scripture) by the Spirit through human authors (2 Tim 3:16–17; 2 Pet 1:20–21).

Reading cue: Arrows flow from God to text, not from community to text. The church/synagogue recognises Scripture; it does not create it.

Ring 2: Canon (Recognition of the Books God Gave)

- OT canon emerging within Israel’s history (the Law/Prophets/Writings pattern; Luke 24:44).

- NT canon recognised by the apostolic churches: Gospels/Acts, Pauline letters, General Epistles, Revelation—circulated, copied, read publicly, tested for apostolicity, orthodoxy, catholic usage, and antiquity (1 Thess 5:27; Col 4:16; 2 Pet 3:15–16).

Reading cue: Solid arrows show recognition milestones; dashed arrows show usage/citation links (e.g., Fathers quoting NT books widely).

Ring 3: Transmission & Preservation (Manuscripts)

- OT: Hebrew Masoretic tradition (Tiberian pointing), evidence from Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), the Samaritan Pentateuch, Targums, Septuagint (LXX).

- NT: early papyri, major uncials (e.g., Sinaiticus, Vaticanus, Alexandrinus), minuscules, lectionaries.

Reading cue: This ring is copying over centuries. Expect variant readings (mostly minor). God’s providence used abundance of witnesses to preserve the text.

Ring 4: Textual Criticism, Translation, and Today’s Bible

- Textual criticism compares manuscripts to identify the earliest recoverable wording.

- Translation renders that text into receptor languages via formal/optimal/dynamic equivalence.

- Publication & Use places the Bible in the hands of the church for reading, preaching, discipleship, mission.

Reading cue: The arrows here point from text to language to reader, with side-panels noting translation philosophies and major translation families.

Timeline rail (bottom): Moses → Prophets → Post-exilic scribes → Second Temple period (DSS/LXX) → Christ & Apostles → Early church copying → Late antique & medieval transmission → Reformation vernaculars → Modern critical editions and translations. Use the rail to locate each panel in time.

3) Legend—Colours, Lines, and Markers

- Colours = category

Gold = Revelation/Inspiration;

Blue = Canon;

Green = Transmission/Preservation;

Purple = Textual Criticism;

Teal = Translation/Publication;

Grey = Methods/notes. - Solid arrows = causal/derivational flow (e.g., God inspires → church recognises → scribes transmit).

- Dashed arrows = cross-links (e.g., a NT book quoted by Fathers; LXX used in the NT).

- Superscripts/labels mark key exemplars (e.g., 1QIsaᵃ; ℵ, B; NA28/UBS5; MT; LXX).

Reading the legend first prevents you from mistaking, say, LXX (a translation used in the NT era) for the inspired autographs themselves.

4) A 20-Minute Reading Plan (First Pass)

- Start at Revelation & Inspiration (center). Read 2 Tim 3:16–17 and 2 Pet 1:20–21.

- Move to OT Canon: Law/Prophets/Writings (Luke 24:44). Note public reading and prophetic deposit (Deut 31:24–26; Josh 24:26).

- Shift to NT Canon: Gospels/Acts → Paul → General Epistles → Revelation. Watch the usage arrows (public reading, church lists, citations).

- Follow to Transmission:

- OT: MT, DSS, LXX, Targums, Samaritan Pentateuch.

- NT: papyri, uncials, minuscules.

- Open Textual Criticism: why variants occur; how comparison works; why conclusions are high-confidence for virtually all verses that matter.

- Finish with Translation & Today’s Bibles: translation philosophies, major English lines (Tyndale → KJV → NKJV; RV/ASV → RSV → ESV; NASB; NIV; CSB; etc.), and how to choose/compare.

5) Worked Examples (Read the Chart Like This)

A) Isaiah in the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Masoretic Text

- What you’ll see: an arrow linking 1QIsaᵃ (Great Isaiah Scroll) to the Masoretic tradition.

- How to read it: this shows substantial stability of the Hebrew text across centuries, with expected minor differences (orthography, small slips).

- Takeaway: Preservation is providence plus plurality (many witnesses), not a myth of perfect copying.

B) New Testament: From Papyri to Printed Greek

- What you’ll see: a stream from early papyri (2nd–3rd cent.) → great uncials (4th–5th) → minuscules (later) → printed editions (Erasmus/Stephanus/Beza → TR; modern critical NA/UBS).

- How to read it: the chart distinguishes textual bases (e.g., TR/Byzantine vs. eclectic NA/UBS) and notes that substantial doctrinal content is unchanged—differences rarely affect doctrine and are footnoted in good translations.

C) The LXX’s Role

- What you’ll see: the Septuagint (LXX) as a Greek translation used among Jews and cited in the NT.

- How to read it: LXX is not the autograph, but a significant witness to OT text and an aid for understanding first-century quotations and wording.

6) Exegesis Layer (Why the Chart Stays Text-First)

Original Language Anchors (sample prompts to keep definitions contextual)

- Hebrew: torah (law/instruction), nĕbî’îm (prophets), ketûbîm (writings); kātav (write).

- Greek: graphē (Scripture), theopneustos (God-breathed, 2 Tim 3:16), pheromenoi (“carried along,” 2 Pet 1:21), kanōn (rule/measure, later usage).

Rule: lexical entries help, but context defines meaning. The chart nudges you to read whole pericopes, not cherry-pick glosses.

Grammar/Syntax Cues

- 2 Tim 3:16 explicitly treats Scripture (not merely prophetic moments) as God-breathed and sufficient.

- 2 Pet 1:20–21 guards against private origin; Scripture comes by Spirit-carried men.

- NT usage of OT demonstrates functional canon already in the first century.

Textual-Variant Discipline

- Significant variants are flagged where meaning plausibly shifts (e.g., endings/omissions in select passages).

- Most variants are spelling/order and do not change sense. Conservative handling: note, weigh, footnote—while maintaining confidence in the established text.

7) Canon Recognition (What the Chart Means by “Recognise”)

- Old Testament: Israel’s Scriptures were received as they arose (e.g., Deut 31:26), then acknowledged as the Law and the Prophets (Luke 24:44).

- New Testament: Churches read apostolic writings publicly (1 Thess 5:27), collected and circulated letters (Col 4:16), and treated them as Scripture (2 Pet 3:15–16).

- Historical lists and Fathers’ citations reflect recognition; they don’t bestow inspiration.

Key balance: “The church’s fallible recognition of Scripture” vs. “Scripture’s infallible authority from God.”

8) Textual Criticism (Why It Serves, Not Threatens, Authority)

- Goal: recover the earliest reachable text by comparing witnesses.

- Tools: external evidence (age, geography, text-type), internal evidence (authorial style/context), and conservative canons of probability.

- Outcome: a highly stable text; where uncertainty remains, good Bibles mark it so readers aren’t misled.

Pastoral line on the chart: “Because God preserved His word across many independent lines, we can test and confirm it; our confidence rests in God’s providence and the mass of evidence.”

9) Translation (From Source Text to Your Bible)

- Philosophies:

- Formal equivalence (word-for-word leaning; e.g., ESV, NASB, LSB);

- Optimal/mediating (CSB, NIV);

- Functional/dynamic (thought-for-thought leaning).

- Process: base text (Hebrew/Aramaic MT with LXX/DSS notes; Greek NA28/UBS5/Byzantine notes), translator committee, review, footnotes, cross-refs, publishing.

- Guidance panel on the chart: use one primary translation for memorisation/study (ESV per your preference) and compare others for nuance; keep an interlinear or original-language tools handy for word-study checks.

10) Practical Workflow (Turn the Chart into a Repeatable Study)

Use this five-move loop:

- Pick a node: e.g., New Testament Canon.

- Collect texts: 1 Thess 5:27; Col 4:16; 2 Pet 3:15–16; Luke 1:1–4; Rev 1:3; 22:18–19.

- Trace recognition: how were these writings used/received? what do the arrows show (public reading, circulation, citations)?

- Connect to transmission: which early witnesses preserve these books (papyri/uncials)?

- Synthesize & apply: one sentence of doctrine; three lines of practice (read publicly; copy and teach; guard the text; translate faithfully).

Quality check (print this):

- I started from revelation/inspiration (not community preference).

- I followed recognition, not creation, of canon.

- I accounted for preservation via multiple witnesses.

- I used textual criticism as a servant, not a master.

- I explained translation choices and why my church uses X.

11) FAQs (Search-Oriented)

Q1: Did the church decide the canon?

No. God inspired the books; the church recognised them. Historical lists reflect that recognition.

Q2: If scribes made mistakes, is the Bible still reliable?

Yes. With thousands of manuscripts across centuries and regions, we can compare and recover the original reading with very high confidence. Differences rarely affect meaning, and are marked.

Q3: Which translation is “best”?

Choose a transparent, committee-produced translation anchored to standard critical texts (with notes), suitable for study and public reading. ESV fits your specified use; compare NASB/CSB/NIV for nuance.

Q4: What about the LXX and DSS—do they change the OT?

They illuminate the OT text and its ancient reception. Where differences arise, translators and scholars weigh evidence and context; many modern Bibles note significant places.

Q5: Does textual criticism undermine inerrancy?

No. Inerrancy applies to the autographs; textual criticism helps us locate their wording. Preservation by abundance is a mark of God’s providence.

12) Representative Scripture Index (ESV)

- Revelation & Inspiration: 2 Tim 3:16–17; 2 Pet 1:20–21; Heb 1:1–2; Jer 1:9; Exod 34:27–28

- Canon & Public Reading: Deut 31:24–26; Josh 24:26; Luke 24:44; 1 Thess 5:27; Col 4:16; 2 Pet 3:15–16; Rev 1:3; 22:18–19

- Preservation: Ps 119:89; Isa 40:8; Matt 5:18; 24:35; 1 Pet 1:24–25

- Use: Neh 8:1–8; 1 Tim 4:13; 2 Tim 4:1–2; Acts 17:11

13) Final Study Counsel

Keep the chart beside your Bible. Each session, pick one panel (e.g., NT Canon or OT Transmission), run the five-move loop, and write one doctrinal sentence plus three practical implications for your church’s reading and teaching. Over time you’ll build a clean, evidence-aware understanding of how God’s word came to us—strong enough to teach, gentle enough to reassure, and faithful to Scripture.